When I first got to Kathmandu, my favorite thing to do was pick a point on my phone’s map and just start walking. It astonished me how quickly the thrilling, if sometimes overwhelming, honking and bustle of the city receded. After an hour on foot, I would be in Newari villages otherwise inaccessible to vehicles other than the most intrepid motorbikes. Women sat outside weaving, and the small roads were full of ducks and goats. On my first walk, I met an elderly woman who took me to her home. It sat on a hillside overlooking the Nakhu River. The loudest noise was the wind in the rice fields.

Observing the stark differences between daily life in Kathmandu compared to just a few miles away made me start to think about distance and connection in relative terms, shaped as much by infrastructure as by actual miles. My work at The Story Kitchen has made me think a lot about distance and connection between people, too.

In the past month I’ve had the privilege of tagging along with colleagues as they tape and film interviews with women who were affected by Nepal’s civil war. I spend these interviews trying to listen, my pen only able to catch fleeting words like “blood,” “pain,” and “disappeared,” before the conversation flows on, faster than I can understand. My notes often read like jagged, bleak poems when I look back at them. It’s surreal and unmooring to know that I may be listening to a woman divulging deep trauma but lack the language skills to empathize in the moment. I struggle with questions about what my role is and whether my presence is helpful, harmful, or neutral.

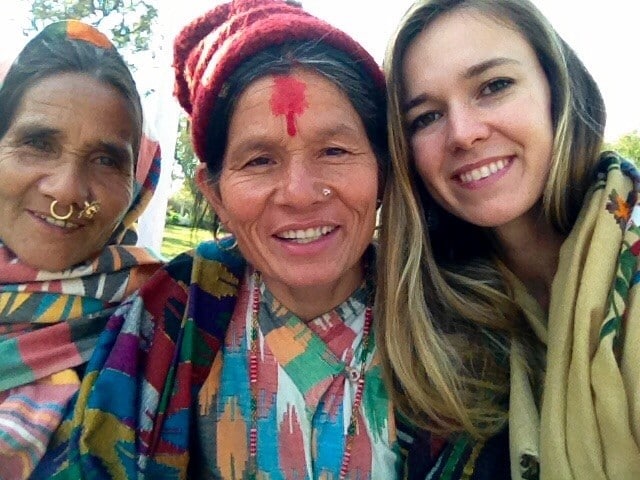

These experiences have made me so grateful for my colleagues who sit down with me afterward and help me understand and process, and for the shopkeepers in my neighborhood whom I buy tea and samosas from, who are generous with my attempts to speak and always willing to explain. They remind me that there are teachers everywhere. I hope their example will make me a more compassionate and patient teacher in the future. I spent Christmas Eve on a field visit in the Terai region. We were hosting a “Storytelling for Empowerment” workshop with women who had survived violence during the civil war. We had gathered to sing and dance, as we did every night of the workshop. I was a little homesick. I decided to video call my mom, perhaps to ease the dissonance within me that was building after a week of absorbing these women’s stories of suffering, after entering their worlds through their words and feeling how different their experiences were from my own.

After a couple seconds of “connecting,” my mom’s face appeared. I gave a little squeak and yelled out to the room in my blunt Nepali, “Mero aama (my mother)!” The reactions from the women were instantaneous. They gathered around the phone, laughing and eagerly passing it around. They ordered me to dance and held up the phone for my mom to watch. A woman who had struggled to express herself all week began to sing a clear, haunting song directly into the phone, causing the room to hush. I saw that my mom’s eyes were leaking.

Afterward, I told this woman that her song had been so beautiful that it moved my mom to tears. She told me that she had been singing her pain and that my mom must have been able to understand that even if she couldn’t understand the words. At this mid-year point, I am full of questions about what we can do in the face of other people’s pain. One thing I feel sure about, though, is that I am thankful to be on a fellowship that values the importance of human connection across disparity.